at least i found out what it can do. also, at least i finally refactored.

problem

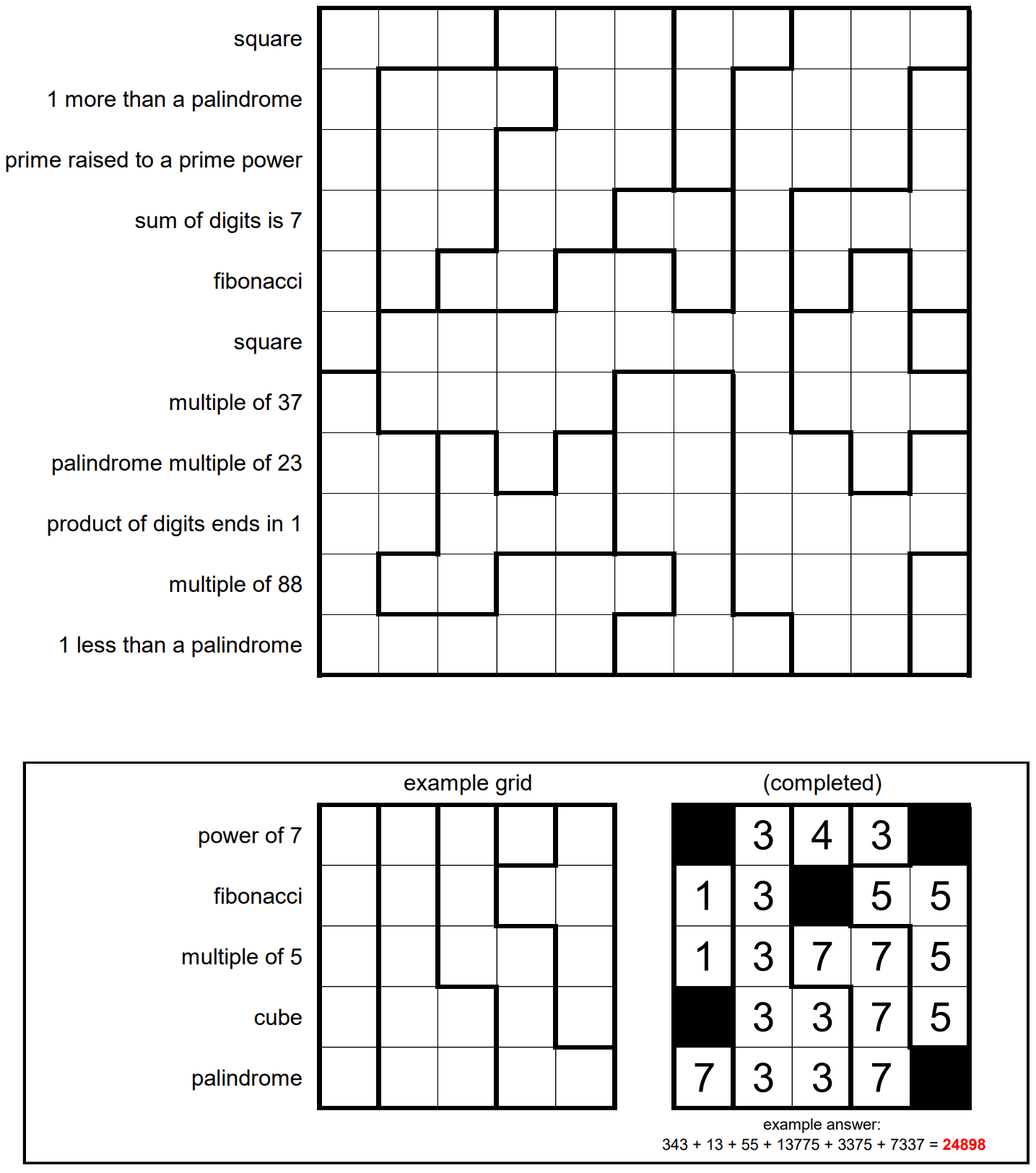

the 11-by-11 grid below has been divided into various regions. shade some of the cells black, then place decimal digits into the remaining cells. shading must be sparse: no two black cells can be adjacent (sharing an edge). black cells can also act as region boundaries.

every cell within a region must contain the same digit, and adjacent cells in different regions must have different digits. as mentioned above, black cells can break regions up or change which regions are adjacent; see below for an example.

each row has a clue. for each row, form numbers by concatening digits left-to-right, where black cells mark the end of one number and the start of a next. these numbers must all satisfy the clue for that row. numbers must be at least two digits long and cannot begin with a leading zero.

the solution is unique.

solution

inspired by others solving number puzzles using z3, i tried. the problem is, it can’t do math constraints. z3 only knows basic arithmetic operations, making it useless for any constraints that involve number theory…which is basically all the constraints.

fine, i’ll do it myself. this puzzle has a three main parts:

- shading some cells black

- filling the remaining regions with numbers

- satisfying row constraints

and the puzzle also seems to be pretty independent row-by-row. so, let’s see if we can solve the puzzle by solving row-by-row. suppose we already have the first $k$ rows solved; how do we proceed to extend this to a solution with the first $k + 1$ rows solved?

- find all valid shadings of that row and extend the $k$-row shading

- for each shading, find how regions are connected

- some regions’ values will be forced by the previous $k$ rows, some won’t

- fill in the remaining regions and find solutions that satisfy row constraints

this is a pretty involved problem. let’s create a Puzzle class to store our information in.

regions = np.array([[0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3],

[0, 4, 4, 4, 1, 1, 2, 3, 3, 3, 6],

[0, 4, 4, 1, 1, 1, 2, 3, 3, 3, 6],

[0, 4, 4, 1, 1, 5, 5, 3, 6, 6, 6],

[0, 4, 1, 1, 3, 3, 5, 3, 6, 7, 6],

[0, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 7, 7, 8],

[9, 3, 3, 3, 3, 11, 11, 3, 7, 7, 7],

[9, 9, 10, 3, 10, 11, 11, 3, 3, 7, 3],

[9, 9, 10, 10, 10, 11, 11, 3, 3, 3, 3],

[9, 10, 10, 9, 9, 9, 11, 3, 3, 3, 12],

[9, 9, 9, 9, 9, 11, 11, 11, 3, 3, 12]])

constraints = [is_square,

palindrome_plus_one,

is_prime_power,

sum_to_7,

is_fibonacci,

is_square,

multiple_of_37,

palindrome_multiple_of_23,

digital_product_mod_10_is_1,

multiple_of_88,

palindrome_minus_one]

constraints_labels = ['square',

'1 more than a palindrome',

'prime raised to a prime power',

'sum of digits is 7',

'fibonacci',

'square',

'multiple of 37',

'palindrome multiple of 23',

'product of digits ends in 1',

'multiple of 88',

'1 less than a palindrome']

class Puzzle():

def __init__(self, regions, constraints, constraint_labels):

self.regions = regions + 1 # needed later on to use skimage.measure.label()

self.constraints = constraints.copy()

self.constraint_labels = constraint_labels.copy()

self.N = len(self.constraint_labels)

self.grid = np.ndarray(shape=(self.N, self.N), dtype=int)

self.grid.fill(-2)

self.splits = self.valid_splits(self.N)

self.solution = None

self.search_space = 0

in particular, constraints is a list of functions. the implementation of these number-theoretic functions is made easier with sympy, which has functions for number theory. for most of these functions, their implementation is straightforward, especially with sympy. however, fibonacci is interesting, and we use a trick: $n$ is a fibonacci number if and only if at least one of $5n^2 \pm 4$ is a square.

find valid shadings

the key observation is that the set of valid shadings is the same for each row, and there aren’t that many of them – far fewer than the $2^{11}$ total. if we want to test if a row shading is a valid extension of an existing shading, we can compare the last row of the existing shading with our candidate row shading to see if there are vertically adjacent black cells. here, shadings is a list of zeros and ones, where zeros represent black cells. we use split to represent a valid row shading.

# takes two (same-sized) lists and checks for vertically adjacent black cells

def check_split(self, row, split):

if row is []: # base case: we're shading row 1 so there's nothing to extend

return True

return all([i != 0 or j != 0 for (i, j) in zip(row, split)])

but how do we find the set of valid row shadings? with a bit of recursion. let $w_n, b_n$ represent the number of row shadings of length $n$ that start with a white or black cell, respectively.

- if our first cell is white, then we start off with an $i$-digit number.

- meaning, the the first $i$ cells of our row are white, and the $i + 1$-st cell is black.

- so, our number occupies the first $i + 1$ cells, leaving a row of length $n - i - 1$ that starts with a white cell: $w_{n - i - 1}$ possible shadings.

- we have the constraints $i \geq 2$ since numbers have to be at least two digits long.

- in addition, we have the edge case $i = n$, which gives us the shading of no black cells. since $w_{-1}$ makes no sense we handle it separately by just adding one.

- this gives us $w_n = 1 + \displaystyle\sum_{i = 2}^{n - 1} w_{n - i - 1} = 1 + \sum_{i = 0}^{n - 3} w_i.$

- if our first cell is black, then our second cell must be black. our recurrence is simply $b_n = w_{n - 1}$.

- our base cases are then $w_0 = 1, w_1 = 0, w_2 = 1$.

it suffices to solve the recurrence of $w_n$, since $b_n$ directly follows. subtracting $w_{n - 1}$ from $w_n$ gives $w_n - w_{n - 1} = w_{n - 3}$ so $w_n = w_{n - 1} + w_{n - 3}$. letting $s_n = w_n + b_n$ be the total number of valid shadings we have

\begin{equation} s_n = w_n + w_{n - 1} = 2w_{n - 1} + w_{n - 3} = w_{n - 1} + w_{n - 2} + w_{n - 3} + w_{n - 4} = s_{n - 1} + s_{n - 3} \end{equation}

after using the fact that $2w_{n - 1} = w_{n - 1} + w_{n - 1} = w_{n - 1} + w_{n - 2} + w_{n - 4}.$

from sympy.series.sequences import RecursiveSeq

s = sympy.Function('s')

n = sympy.symbols('n')

splits = RecursiveSeq(s(n - 1) + s(n - 3), s(n), n, [1, 1, 3], start=0)

notably, this sequence doesn’t grow that fast for small values of $n$; in particular $s_{11}$ is only $54$, a far cry from the $2^{11} = 2048$ possible. but to actually find these shadings, we’re going to have to go back to black and white shadings.

def black_splits(self, n):

if n == 1:

return [[0]]

return [[0] + split for split in self.white_splits(n - 1)]

def white_splits(self, n):

result = [] if n < 2 else [[1 for i in range(n)]]

for i in range(2, n):

prefix = [1 for j in range(i)]

result = result + [prefix + split for split in self.black_splits(n - i)]

return result

def valid_splits(self, n):

return self.white_splits(n) + self.black_splits(n)

find connected regions

find all connected components of a graph. do i know how to do this? yes – any graph traversal algorithm will do. will i? of course not – this is python, someone has already done it. in particular, if we assign each cell a (positive) number based on its region and element-wise multiply by the (potentially only partial) shadings grid, the resulting grid will have black cells labeled with zero and white cells labeled with their region id.

def connected_regions(self, candidate_split):

filled_split = np.array(candidate_split) # candidate_split is when we only have a partial shading

return skimage.measure.label(self.regions[:filled_split.shape[0],:] * filled_split, connectivity=1) # zeros will be considered background, and will have label 0

fill regions with numbers

let’s first examine how not to fill regions. we know cells of the same region have the same value, and adjacent cells of different regions don’t. here, candidate_solution represents what we’ve filled our cells with, while regions is the grid with our regions. for candidate_solution, black cells are represented by -1, not zero since zero can also be a digit.

def conflicting_regions(self, regions, candidate_solution=None):

if candidate_solution is None:

return False

return any([self.conflicting_cells(regions, candidate_solution, i, j) for (i,j),_ in np.ndenumerate(candidate_solution)])

def conflicting_cells(self, regions, candidate_solution, x, y):

return any([self.conflicting_pair(regions, candidate_solution, x, y, i, j) for (i,j) in self.adj(regions, x, y)])

def conflicting_pair(self, regions, candidate_solution, x, y, i, j):

if candidate_solution[x,y] != -1 and candidate_solution[i,j] != -1: # we don't care if one of the cells is black

return candidate_solution[x,y] == candidate_solution[i,j] and regions[x,y] != regions[i,j] \

or candidate_solution[x,y] != candidate_solution[i,j] and regions[x,y] == regions[i,j]

return False

def adj(self, grid, x, y):

m, n = grid.shape

return [(i+x, j+y) for i,j in [(-1,0),(0,-1),(1,0),(0,1)] if i+x >=0 and i+x < m and j+y >=0 and j+y < n]

we also have to check if we fill a cell directly to the right of a black cell with zero. we also cannot fill the first cell in a row with zero.

def check_nonzero(self, row, index):

if index == 0:

return True

return row[index - 1] == -1

def check_nonzero_region(self, row, region):

return any([self.check_nonzero(row, index) for index in region])

okay. now we can start filling in cells. here, extend_solution takes in a partial solution candidate_solution, and extends the solution by one more row.

def extend_solution(self, candidate_split, candidate_solution=None): # candidate_solution does not have the extended row, candidate_split does

row_index = len(candidate_split) - 1

regions = self.connected_regions(candidate_split)

original_region = regions[:-1,:]

extended_region = regions[-1,:]

new_row = np.array([-2 for i in range(self.N)])

new_regions = collections.defaultdict(list) # dictionary of new regions

for i,region in enumerate(extended_region):

if region == 0:

new_row[i] = -1

else:

region_value = self.region_value(candidate_solution, original_region, region)

if region_value == 0 and self.check_nonzero(new_row, i):

return []

elif region_value != -2:

new_row[i] = region_value

else:

new_regions[region].append(i)

result = self.solve_row(new_row, new_regions, self.constraints[row_index])

if candidate_solution is None:

return [np.reshape(row, (1, self.N)) for row in result if not self.conflicting_regions(regions, np.reshape(row, (1, self.N)))]

return [np.append(candidate_solution, [row], axis=0) for row in result if not self.conflicting_regions(regions, np.append(candidate_solution, [row], axis=0))]

def region_value(self, candidate_solution, regions, region_number):

if candidate_solution is None:

return -2

result = np.where(regions == region_number)

if result[0].size == 0:

return -2

return candidate_solution[result[0][0], result[1][0]]

well, extend_solution does include code that solves a row, so, what’s most important to us right now is this snippet:

regions = self.connected_regions(candidate_split)

original_region = regions[:-1,:]

extended_region = regions[-1,:]

new_row = np.array([-2 for i in range(self.N)])

new_regions = collections.defaultdict(list) # dictionary of new regions

for i,region in enumerate(extended_region):

if region == 0: # remember, region of zero means it's a black cell. stare at the implementation of connected_regions() again

new_row[i] = -1

else:

region_value = self.region_value(candidate_solution, original_region, region)

if region_value == 0 and self.check_nonzero(new_row, i):

return []

elif region_value != -2:

new_row[i] = region_value

else:

new_regions[region].append(i)

the function region_value returns a valid digit of the region with id region is in the origial candidate solution, and -2 if it’s a new region. this allows us to force cells connected to prior regions, while also keeping track of the regions we need to fill in new_region.

as an aside: i just want to talk to the person who wrote np.where. why, oh, why, are the indices given in the form ([i_1, i_2, ... , i_n], [j_1, j_2, ... , j_n]) instead of [(i_1, j_1), (i_2, j_2), ... , (i_n, j_n)]? it makes no sense.

anyhow. we can now fill the new regions.

def fill_region(self, row, cells, value):

result = np.copy(row)

for cell in cells:

result[cell] = value

return result

you may have noticed we don’t check for illegal zero placements in fill_region. that’s okay – i didn’t forget about it.

(by the way – if we instead didn’t worry about filling in number regions until the very end; that is, if we filled out all possible shadings of the board first before filling out numbers, i don’t even know how many board states we could go through. the upper bound is $54^{11}$, of course, but i tried to compute the exact amount by running it on a compute server for over a week and it timed out. so yeah. we really do need to be as restrictive as possible.)

solving the row

it should now be clear how to solve a row: fill in the regions that need to be filled, then check if the row satisfies its constraint. we can do this by backtracking – filling in one region at a time – to recursively solve the row. if a row has cells not forced by prior connected regions, it has value -2 to indicate it has yet to be filled.

def solve_row(self, row, new_regions, constraint):

if not new_regions:

return [np.copy(row)] if self.check_constraint(row, constraint) else []

region,cells = next(iter(new_regions.items()))

newer_regions = dict(new_regions)

del newer_regions[region]

result = []

for value in range(10):

if value == 0 and self.check_nonzero_region(row, cells): # hey look, there's our illegal zero check!

continue

candidate_row = self.fill_region(row, cells, value)

if self.check_constraint(candidate_row, constraint):

result = result + self.solve_row(candidate_row, newer_regions, constraint)

return result

def check_constraint(self, row, constraint): # also includes the no single-digit numbers constraint, but this should've been taken care of when generating splits

return all([constraint(i) and i >= 10 for i in self.get_numbers(row)])

def get_numbers(self, row):

result = ''.join(map(str, row))

result = [int(s) for s in result.split('-1') if s and s.find('-2') == -1]

return result

now it should be clear how extend_solution works: solve the row given candidate_solution, then append all the rows compatible with candidate_solution into a new list of candidate solutions extended one more row. this is also why we don’t check for conflicting region values in solve_row – we wait to see if any values conflict in the extended solution grid at the end of extend_solution.

to solve the whole puzzle, we simply to a depth-first search of possible solutions, solving one row at a time. our stack stores tuples of (partial shading, [partial solutions with that shading]).

# simple stack search, pruning when needed

def solve(self):

if self.solution is not None:

print_grid(self.solution, self.regions, self.constraint_labels)

print(f'\nAnswer: {self.answer()}\nNodes searched: {self.search_space}')

return

result = []

stack = queue.LifoQueue()

stack.put(([], [None]))

while not stack.empty():

candidate_split, candidate_solutions = stack.get()

if len(candidate_split) == self.N:

result = result + candidate_solutions

else:

for split in self.splits:

if len(candidate_split) == 0 or self.check_split(candidate_split[-1], split):

new_split = candidate_split + [split]

new_solutions = []

for candidate_solution in candidate_solutions:

new_solutions = new_solutions + self.extend_solution(new_split, candidate_solution)

if new_solutions:

stack.put((new_split, new_solutions))

self.search_space = self.search_space + 1

if len(result) == 0:

print('Failed to find solution. Check your constraints or regions, or debug your code.')

elif len(result) > 1:

print("Found multiple solutions. Check your constraints or regions, or debug your code, the latter being more likely.")

print("Make sure you're accounting for ALL the constraints.")

else:

self.solution = result[0]

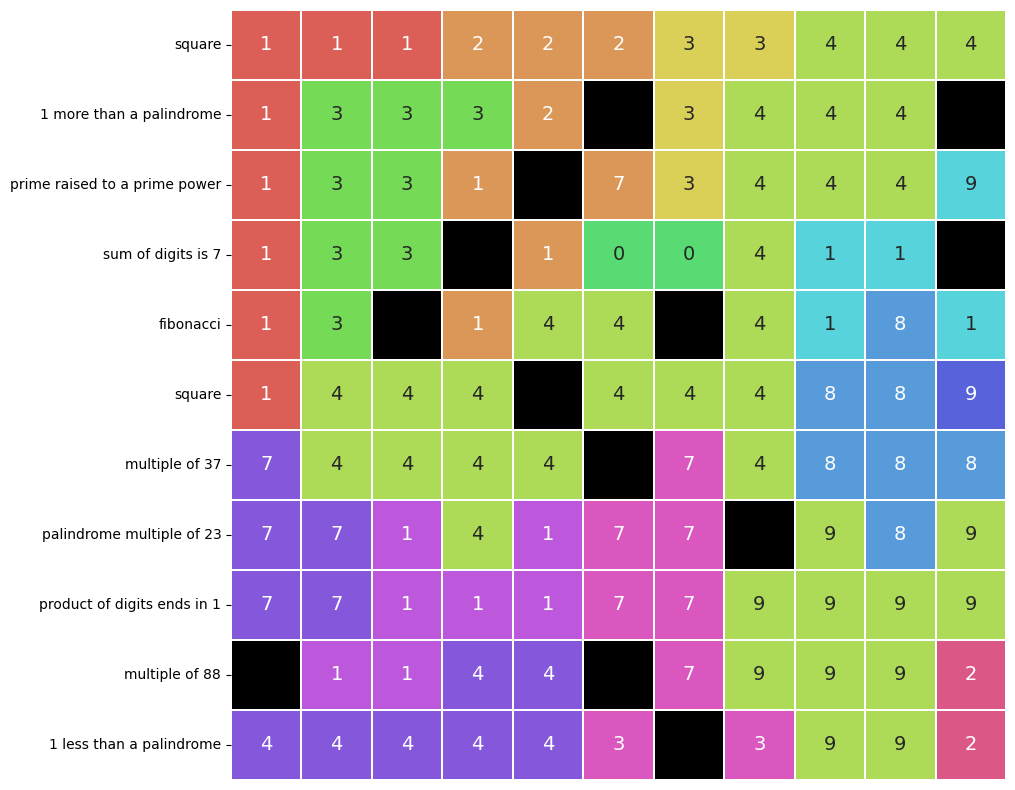

print_grid(self.solution, self.regions, self.constraint_labels)

print(f'\nAnswer: {self.answer()}\nNodes searched: {self.search_space}')

def answer(self):

return np.array(list(itertools.chain(*[self.get_numbers(row) for row in self.solution]))).sum()

def print_grid(grid, regions, constraints):

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 10))

x = np.array(grid.astype('str'))

x[x == '-1'] = '' # shaded cells

x[x == '-2'] = '?' # unfilled cells. should not happen

num_colors = len(np.unique(regions))

for i, j in zip(np.where(x == '')[0], np.where(x == '')[1]):

regions[i,j] = 0

ax = sns.heatmap(regions, annot=x, cbar=False, cmap=[(0, 0, 0)]+sns.color_palette('hls', num_colors), fmt='', linewidths=0.25, xticklabels=False, yticklabels=constraints, annot_kws={'size':14}) # the (0, 0, 0) is so shaded cells show up as black

plt.show()

despite its simplicity, this search is incredibly efficient because of how heavily we enforce our constraints: enforcing constraints at every row instead of waiting until the entire grid is shaded and filled allows us to catch bad solutions incredibly early. in fact, keeping track of our search_space, we see that we only needed to search an shockingly low 41 – forty-one – nodes to find our solution. this allows our code to run in less than thirty seconds. not bad, given the fact that i probably needlessly copied my grids, and i kept switching between storing grids as lists of lists and np.ndarray, adding even more overhead due to needing to convert.

# # solves the example puzzle

# test_puzzle = Puzzle(test_regions, test_constraints, test_constraints_labels)

# test_puzzle.solve()

puzzle = Puzzle(regions, constraints, constraints_labels)

puzzle.solve()

look how pretty it is! a lot prettier than last month’s answer, that’s for sure.