feeling a bit boxed in

problem

pick two points in a square, uniformly at random. what is the probability that the circle formed by taking the two points as a diameter is completely contained in the square?

solution

working with random coordinates $\left(x_1, y_1\right), \left(x_2, y_2\right)$ doesn’t really take us anywhere. we switch to looking at two other things that can define a circle:

- center of the circle $O = (h, k)$

- diameter length $d$ of the circle

in hopes of getting something useful. the distribution of $d$ can be found, after a bit of manipulation from page 3 of this paper, to

\begin{equation} f_D(d) = \begin{cases} 2d\left(d^2 - 4d + \pi\right) & \text{if }d \leq 1 \newline 2d\left[4\arcsin\left(\dfrac{1}{d}\right) + 4\sqrt{d^2 - 1} - d^2 - \pi - 2\right] & \text{if }1 < d \leq \sqrt{2} \newline 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \end{equation}

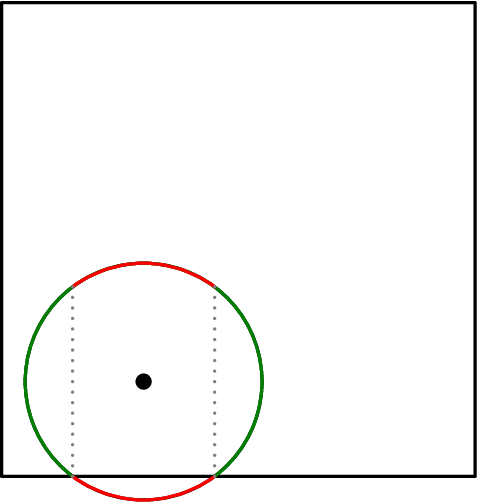

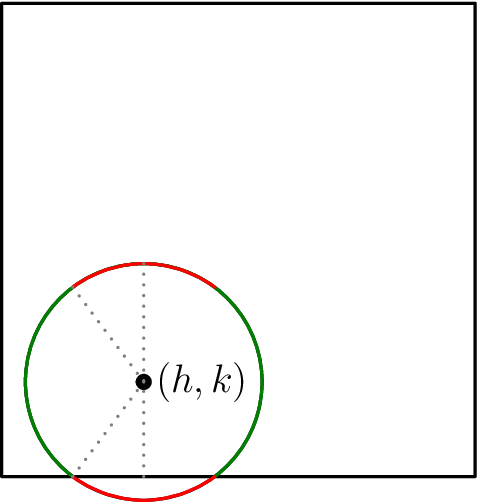

so it remains to deal with $O$. note that, for fixed $d$, $O$ completely determines whether the circle stays contained or not: the circle defined by $O$ and $d$ is contained inside the square if and only if $\frac{d}{2} \leq h, k \leq 1 - \frac{d}{2}$. can we just say the probability the circle is contained is $(1 - d)^2$ then? no – $O$ is not uniformly distributed. if the circle exits the square, the arc outside the square corresponds to diameters that can’t actually be formed. for example, if a quarter of the circle is outside the square, it means there are certain point pairs that don’t work as diameters. so, for a given $O$ and $d$, draw the circle and think: out of all diameters, which ones have both endpoints inside the circle? shown below is the general case, with the illegal region in red. (the region at the top of the circle is red because any endpoint there would correspond to the other endpoint being outside the square.)

let the probability of the midpoints with $\frac{d}{2} \leq h, k \leq 1 - \frac{d}{2}$ have arbitrary “scaled density” $\pi$, corresponding to being able to pick all points along one-half of the circle to be an endpoint of a diameter. it remains to think, how much “scaled density” do points outside the central square have? $\pi - \theta$, where $\theta$ is the length of the arc outside the square. so, if $0 \leq k < \frac{d}{2}$ and $\frac{d}{2} \leq h \leq 1 - \frac{d}{2}$, the “scaled density” is $\pi - 2\arccos\left(\frac{2k}{d}\right)$. integrating over $k$, then multiplying by $4(1 - d)$, gives the “scaled density” over all edges (but not the four $\frac{3}{2}$-by-$\frac{d}{2}$ square corners) of the square.

\begin{equation} 4(1 - d)\displaystyle\int_0^\frac{d}{2} \pi - 2\arccos\left(\dfrac{2h}{d}\right)\,dh = 2d(1 - d)(\pi - 2) \end{equation}

we must be careful with the corner cases. without loss of generality let $0 \leq h, k < \frac{d}{2}$. we claim that there are points in this square that $O$ cannot be. if the circle defined by $O$ and $d$ contains the corner $(0, 0)$, then more than half the circle is outside the square. but then, there’s no legal diameter of the circle, contradiction (figure shown below). so, $O$ must be at least $\frac{d}{2}$ distance from the origin, which corresponds to $h^2 + k^2 > \left(\frac{d}{2}\right)^2$.

again by symmetry, multiplying the relevant integral by $4$ gives the “scaled density” over all corners:

\begin{equation} 4\displaystyle\int_0^\frac{d}{2} \int_\sqrt{\left(\frac{d}{2}\right)^2 - h^2}^\frac{d}{2} \pi - 2\arccos\left(\dfrac{2h}{d}\right) - 2\arccos\left(\dfrac{2k}{d}\right)\,dk\,dh = d^2(\pi - 3) \end{equation}

so adding in the center cases’s “scaled density” of $\pi(1 - d)^2$ we get a probability of

\begin{equation} p(d) = \dfrac{\pi(1 - d)^2}{d^2 - 4d + \pi} \end{equation}

then using law of total probability we have

\[\begin{align*} \int_0^\sqrt{2} p(d) f_D(d)\,\mathrm{d}d &= \int_0^1 2d\left(d^2 - 4d + \pi\right)p(d)\,\mathrm{d}d \\ &= \int_0^1 2\pi d(1 - d)^2\,\mathrm{d}d = \mathbf{\dfrac{\pi}{6}} \end{align*}\]and we are done.

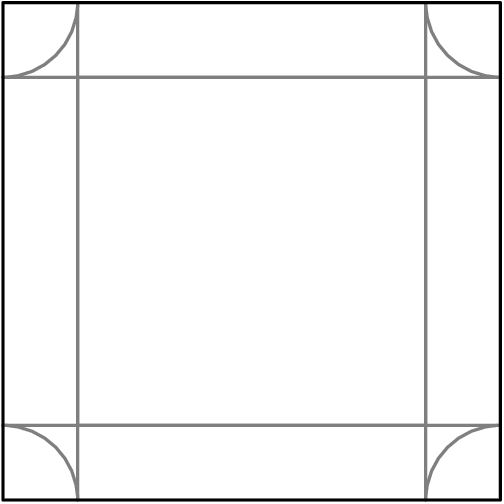

the official solution involved less calculation. while the first probability should be clear as an integral, the second probability of $\frac{3}{4}$ might be better understood in the reverse direction. if you know that your diameter (vector extended past the circle’s center) must lie within the square, then your circle center must lie within the square scaled down by half, where the center of scaling is your originally chosen diameter endpoint. thus, the ratio of the smaller square, the successful region, to the larger one, is $\frac{1}{4}$. in other words, if you fix one perimeter point, then the region of valid diameter endpoints is a circle with twice the radius of the region of valid center points and has four times the area, hence the multiplying by four.

maybe i really should go back and try and make my solutions as calculation-free as possible after solving. the issue is, not every problem has such a simple solution so i get paranoid if one exists at all.

extension to higher dimensions

let’s extend the official solution to $n$ dimensions. the integrand of $\pi y^2$ comes from the area of the circle, since if the perimeter point is inside the circle with radius $y$ centered at $(x, y)$ with $x \geq y$ then the circle will be completely contained within the square. the higher-dimension analogue of this is the center point at $(x_1, x_2, \cdots , x_n)$ with (without loss of generality) $x_1 \leq x_2 \leq \cdots \leq x_n$. then, the surface point would have to be contained in the $n$-sphere of radius $x_1$. the volume of this sphere is $V_n x_1^n$ where $V_n$ is a constant depending on n. from here, we get rid of the ordering of the $x_i$’s and note that the radius of the sphere is simply the minimum of the $x_i$’s given $0 \leq x_i \leq \frac 12$ for all $i$. from here on out, we scale by $2$ so we can work with the nice constraint $0 \leq x_i \leq 1$. then, the density of the minimum of a sample of size $n$ drawn from the standard uniform distribution $U(0, 1)$ is $f(x) = n(1 - x)^{n - 1}$ so our integral becomes

\begin{equation} \int_{[0, 1]^n} V_n \cdot \min\left(x_1, x_2, \cdots , x_n\right)^n\,\mathrm{d}M = nV_n \int_0^1 x^n(1 - x)^{n - 1}\,\mathrm{d}x \end{equation}

and now the integrand looks like the (scaled) expected value of a beta distribution with $\alpha = \beta = n$. manipulating a bit further we get

\[\begin{align*} nV_n \int_0^1 x^n(1 - x)^{n - 1}\,\mathrm{d}x &= nV_n\mathrm B(n, n) \int_0^1 \frac{x \cdot x^{n - 1}(1 - x)^{n - 1}}{\mathrm B(n, n)}\,\mathrm dx \\ &= \frac {nV_n}{2} \cdot \frac{2n}{n^2} \cdot \binom{2n}{n}^{-1} = V_n \binom{2n}{n}^{-1} \end{align*}\]and then we’d divide by $2^n$, the volume of the $n$-cube, then multiply by $2^n$ in converting paradigms from “center point and surface point” to “endpoints of a diameter” by the same reasoning as above. we are done.