hexagons are the bestagons

only if you work in $\mathbb Q[\sqrt 3]$.

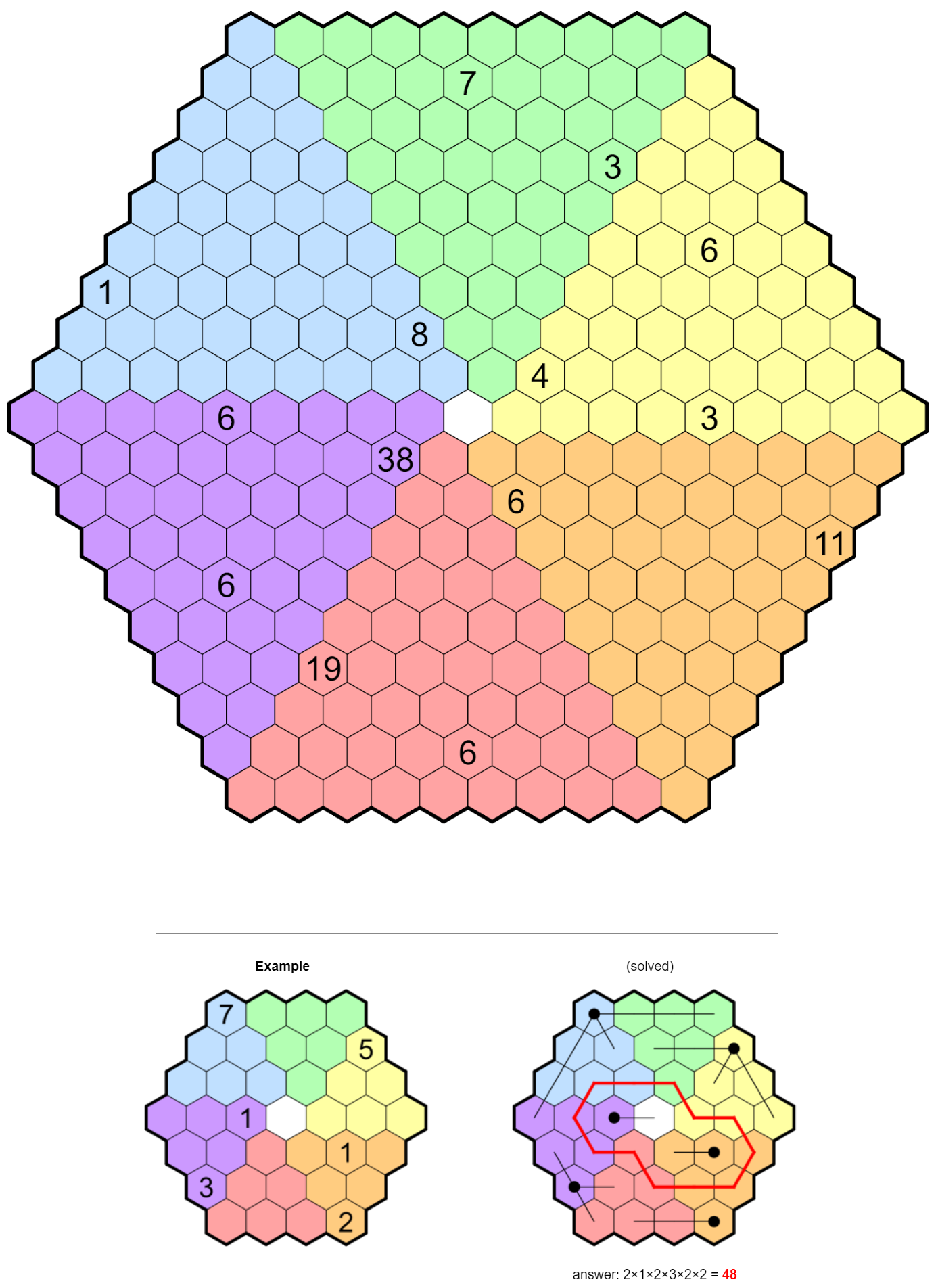

problem

shown below is a hexagonal grid, or hexgrid. it’s similar to a square grid, but each cell of a hexgrid now has six neighbors. some cells are numbered, and these cells contain “fenceposts” at their center. for each post, construct up to six (one for each adjacency direction) fences emanating from the post such that the total length of fence equals the number on the post. fences are straight line segments and only intersect cell borders at right angles; in other words they are straight lines in each of the six adjacent directions. fences end at a cell center, and fences from different posts may not touch or intersect.

construct fences, as in the example above, in such a way that it is possible to draw a closed loop through the centers of a subset of the remaining empty cells. the loop can only make 120-degree turns and must visit each of the six colored regions. finally, the loop must be either rotationally or reflectionally symmetric.

solution: expectation

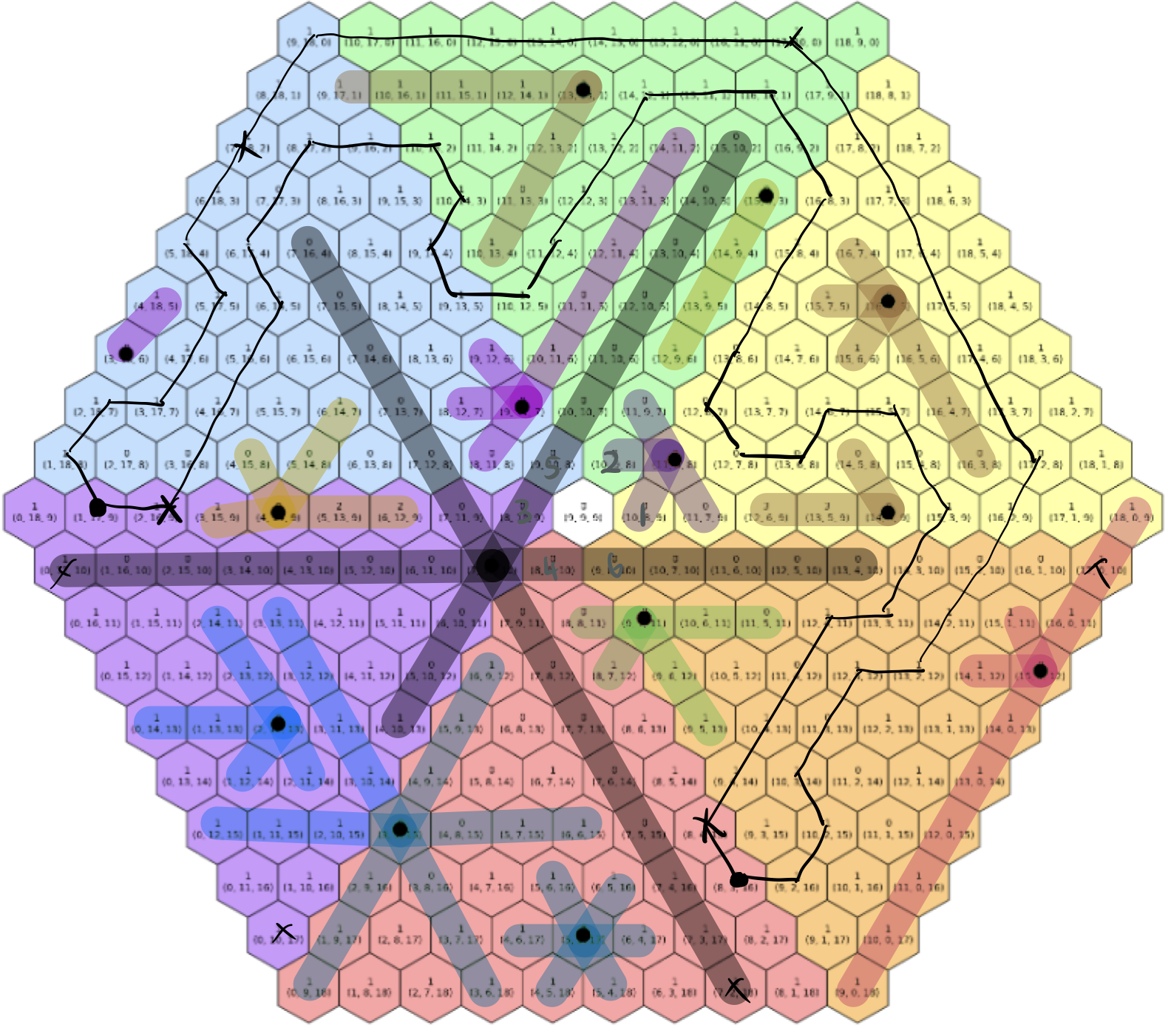

we will be working with hexagonal coordinate systems. for ease of understanding, i used the cube coordinate system. using a two-dimensional coordinate system like skew coordinates will make things ten times faster, but implementation is much easier with cube coordinates.

the grid

is simply a three-dimensional array with each dimension $2N + 1$ in length, where $N$ is the side length of a color’s triangle. it’s also nice since we can assign colors very easily with cube coordinates.

the positive $x$-axis is $30^\circ$ above the cartesian positive $x$-axis, while the positive $y$-axis is $30^\circ$ above the cartesian negative $x$-axis. the positive $z$-axis points straight down.

the adjacency directions are permutations of $(1, -1, 0)$. this is nice since we can define a custom adjacency structure for our array labeling algorithm scipy.ndimage.label which labels connected components. this will be heavily used later on.

for visualization and transformations, we convert cube coordinates $(a, b, c)$ to axial coordinates $(a, b)$, since $a + b + c = 0$ and so $c$ encodes no new information.

constructing fenceposts

for a post with number $n$, the possible fencepost configurations are solutions to $a_1 + a_2 + \cdots + a_6 = n$ in nonnegative integers, where each $a_i$ corresponds to an adjacency direction.

there are a few fast fails we can use to check if a post is even fillable. for each adjacency direction, we can get the extent of empty cells starting from the post; think of this as how far each post can “see.” if the sum of these extents is less than $n$, we cannot fill the post.

we can extend this check to make sure that, after we have filled one post, every other post is still fillable. for instance, certain fills of the post numbered $19$ will result in less than $38$ cells available for the post numbered $38$, and these are also invalid.

checking for cycles

after we fill a post, we want to make sure the configuration results in a symmetric, “rainbow-covering” region, then check if that region yields a cycle. it is actually not that difficult to do this with grid labeling, which will partition all empty cells into connected component. if a component covers the rainbow, then we can test if rotating or reflecting the region will still result in a rainbow-covering region.

for rotational symmetry, the cycle will be symmetric by 60, 120, or 180 degrees; it suffices to check only for 120 and 180 degree symmetry. for 180 degree symmetry, look along the red-green axis line: for each pair of cells $(a, b)$ such that $a$ is on the red portion of that line and $b$ is on the green of it, the center of rotation will be $(a + b) / 2$ and simply intersect the region with the rotated one. for 120 degree symmetry, we keep the red line the same, but now $b$ comes from the yellow part of the yellow-purple axis line. letting $c$ be $b$ rotated $60^\circ$ counterclockwise about $a$, the center of rotation will be $(a + b + c) / 3$ (the center $o$ will be along the perpendicular bisector of $a$ and $b$ such that the angle at $o$ is $120^\circ$; convince yourself these two definitions are equivalent).

for reflectional symmetry, we check each pair of points in the region and reflect the region over their perpendicular bisector.

to check if a region is closed (think of a C-shaped region as a region that is open), we try and find the boundary of the region. usually it is not so simple. however, since we’re on a grid and not in euclidean space, it is simple: for each point in our region, if there exists another point in the region in all adjacency directions, then said point is “surrounded” and is an interior point. otherwise, it is on the boundary. and, if this region is closed, then at some point we should be revisiting points. this is modified depth-first search, and if we ever stop before revisiting, the region is not closed.

to check if this region has a cycle, we can apply pick’s theorem on the axial coordinates of the boundary of the region. if the computed area lines up with the area pick’s theorem gives, then it has a cycle since it’s a simple polygon. (wow, finally found a use for that theorem.)

no, simply checking if there exists an interior point is insufficient to show there is a cycle. counterexample: a “figure-eight” shape, where the two loops only meet at a single point.

note that i don’t check for $120^\circ$ turns at all. too bad! i generate all solutions anyways so this is not a concern.

transformations

rotations and reflections are all linear transformations, with matrix representations in cartesian. since we can convert cube to cartesian, transformations become easy to represent in cube coordinates.

putting it all together

we fill each post in by depth-first search. intuition tells us the larger the post number is, the more “restricting” it will be on the board, so we search in order of post number. so, fill in the 38-post first; every time a fill is successful we proceed onto the 19-post, then the 11-post, and so on. observe the following (theoretical) complexities:

- for each post number $p$, the number of configurations is $\binom{p + 5}{5} = O(p^5)$

- checks for rotational symmetry is $O(N^2)$

- checks for reflectional symmetry is $O(N^4)$, since there can be up to $O(N^2)$ points in a region and you must consider each pair

- for each symmetry check:

- checking if a region is closed and computing the boundary is $O(N^2)$

- computing the area is $O(N^2)$

- so, checking each configuration is $O(N^6)$

at first, this looks quite bad. and, maybe there is room for improvement on checking for reflectional symmetry, but the first few fenceposts are so restrictive recursion depth does not present much of a problem.

solution: reality

usually, at the end of these puzzle-type problems, i post my implementation. i’m not doing that this time – my implementation did not follow all the steps above and is kinda faulty. my solution was computer-assisted rather than computer-generated: i got down to a recursion depth of 6 and manually finished the puzzle.

why? what made my implementation slow? a few things.

incorrect cycle check

my implementation’s cycle check was completely different. it was: partition the complement of the region into its connected components. if there exists a component such that none of the coordinates are a distance $N$ from the origin, then this component is “surrounded” by the region and thus the region contains a cycle. counterexamples to this check are numerous: simply consider any “filled-in” region.

depth-first search order

intuition tells us the larger the post number is, the more “restricting” it will be on the board

and intuition is only partially correct. in reality, the purple, red, and orange regions of the board are heavily restricted, since once the 38, 19, and 11-posts are filled in, almost all configurations of the orange 6-post will fail due to blocking a cycle and very few configurations of the first three posts work. thus, the orange 6-post, and the other posts in the red and purple regions, should actually be higher in the order.

…or, the search should iterate through all posts at each step and check if fills are possible for all of them before proceeding onward. but, that’s a lot of extra work (and cache solutions are…iffy).

forced fills

instead of generating all configurations of the post first, and then failing based on “view range” from the post, filter while generating configurations.

reflectional symmetry checks

maybe there is room for improvement on checking for reflectional symmetry

what are the chances of the symmetry axis not being either one of the axes or one of the adjacency directions? these six directions, represented by multiples of $30^\circ$ to the positive cartesian $x$-axis, are intuitively the most likely axes of symmetry since they always map grid cells to grid cells.

other axes, skew to the natural structure of a hexagonal grid, map many grid cells to non-integer coordinates and so “lose” cells, making it unlikely that a region is symmetric across this axis.

rounding

converting between cube and cartesian coordinates involves multiplying by $\sqrt 3$, so transformations are done in the floating-point numbers, not the integers. but, cells must have integer coordinates, so when getting the result from conversions, we have to check if the result coordinates are close enough to integer coordinates. i ran a profiler, and this actually takes up a huge amount of time, anywhere between 25 and 50 percent of total runtime.

let’s think about the operations we do in transformations:

- calculating centers of transformation is simply averaging, or, dividing, integers

- converting from cube to cartesian involves multiplying by fractions of $\sqrt 3$

- rotation by $120^\circ$ has the rotation matrix take values that are either rational or rational multiples of $\sqrt 3$

- rotation by $180^\circ$ is simply coordinate swapping and taking negatives

- reflection will have the axis be at some multiple of $30^\circ$ to the positive cartesian $x$-axis and thus has the reflection matrix take values that are either rational or rational multiples of $\sqrt 3$

so all our numbers will be in the form $a + b \sqrt 3$, for $a, b \in \mathbb Q$. so, we can work in a field extension $\mathbb Q[\sqrt 3]$ and avoid the mess of floating-point computation!